"A Great Day In Harlem": Remembering the iconic 1958 photo of legendary musicians

Click to watch the video and interview with Benny Golson

Click to watch the video and interview with Benny Golson Sixty years ago this month, Esquire Magazine released its issue featuring what would become an iconic photo: 58 legendary jazz musicians gathered in front of a Harlem townhouse. Now, a new book reveals the story behind the historic image called "A Great Day In Harlem."

Benny Golson is one of the great tenor sax players, a composer of jazz standards like "Killer Joe." Golson was also a member of the elite group of musicians who gathered on that Harlem doorstep in 1958.

"I remember it like it was 24 hours ago," Golson said about that day. "I remember everything about it."

Golson, who'll be 90 next week, had just moved to New York City to join Dizzy Gillespie's band when he was invited to a photo shoot at 17 East 126th St. He didn't know what he was in for. He was stunned.

"All my heroes and then I say to myself, 'What am I doing here?'" Golson said. "Nobody knew who the heck Benny Golson was."

Fifty-eight musicians showed up and the big picture would capture the giants of jazz: Count Basie sitting on the curb, and Dizzy Gillespie with Roy Eldridge, Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, Gerry Mulligan, Gene Krupa, Coleman Hawkins and Sonny Rollins.

Golson described the group as "the cream of the crop." He is one of two surviving musicians from the photograph and the only one still performing.

Jonathan Kane's father, Art Kane, was a hotshot young art director in 1958. He pitched the idea of the picture to Esquire Magazine for its "Golden Age of Jazz" issue.

"The concept here was just really to assemble as many great people as possible," Kane said.

The new book, "Art Kane Harlem 1958" shows frame by frame how the musicians began to gather for the 10 a.m. call time.

"There was no money involved … no stylists around … what you really had were 58 brilliant artists who came for the love of their craft," Kane said.

Kane's vintage contact sheets show there were distractions as he tried to take the big picture such as a horse and buggy going by, street peddlers passing, kids on the curb, and the musicians themselves, who were all excited to see each other.

"I think famously my dad rolled up a New York Times into a megaphone shape and started imploring people to please move up into the steps," Kane said.

But on that day, Benny Golson had no idea what a big deal the picture would become.

"None whatsoever … when the magazine came out I bought it of course," Golson said. "And I turned to the picture and said, 'boy, that's a great picture.' And like all magazines, you keep it for a while and I finally threw it in the trash."

But as Kane explained, people fell in love with the photo instantly. Over time, its impact grew.

"It's really taken on a life of its own," he said.

Art Kane's career as a photographer was launched that day. His future subjects would include Aretha Franklin, Janis Joplin and The Who.

Benny Golson became a composer and arranger, scoring music for TV shows, including "M*A*S*H," "Mission Impossible" and "The Partridge Family." But nothing was quite like the morning he spent on that Harlem doorstep.

"This was unforgettable. Magnum opus … I feel like it was a privilege."

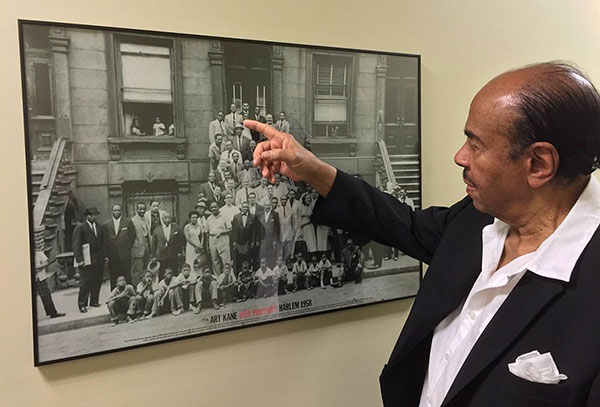

Benny Golson pointing at himself in the Art Kane photograph

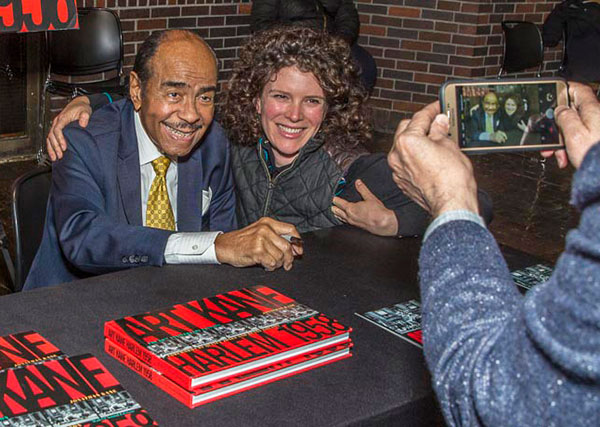

Benny Golson during a book signing for ART KANE - HARLEM 1958

A Great Day In Harlem, Revisited

By Marc Myers

It has long been considered jazz’s most iconic and triumphant image. Photographed by Art Kane, “Harlem 1958” captured 57 jazz greats gathered on the stoop of a Harlem brownstone and on the sidewalk below. Staged loosely as a “class photo,” the image cast jazz musicians in a fresh light and marked a turning point in how jazz was viewed and appreciated. Now known as “A Great Day in Harlem,” the photo was taken on Aug. 12, 1958, and originally appeared in Esquire magazine in January 1959. In the years that followed, the iconic image inspired many copycat group photos of leading writers, rappers and contemporary artists. It was the subject of the 1994 documentary “A Great Day in Harlem” and plays a pivotal role in the 2004 film “The Terminal,” directed by Steven Spielberg.

To commemorate the photo’s 60th anniversary, Wall of Sound Editions will publish “Art Kane: Harlem 1958” on Nov. 12. The 168-page book includes essays by Jonathan Kane, the late photographer’s son and archive executor; saxophonist Benny Golson, one of the photo’s two surviving jazz musicians; and an oral history by Art Kane from the 1994 documentary.

“Harlem 1958” has long been praised for its relaxed formality and Kane’s remarkable ability to corral so many jazz greats, but the photo also marks a significant turning point in jazz’s status in American culture. After the image appeared in Esquire, jazz earned a new level of respect among arts writers and critics, in general-interest magazines and with TV producers. Before 1959, jazz was widely considered subterranean, nocturnal music favored by hipsters, intellectuals and outcasts. Jazz musicians were typically photographed only for jazz magazines and album covers. Coolly aloof, they were often featured playing in smoky clubs or in recording studios. By photographing the musicians in daylight, without their instruments or egos, and having them look directly into the lens, Kane recast jazz artists as accessible and neighborly rather than as detached nonconformists of the counterculture.

The photograph came off as a warm portrait of a welladjusted family of artists. Black and white musicians—male and female, old and young—stood shoulder to shoulder without pretense or any suggestion of cliques. To the naked eye, the musicians were a jovial fraternity of equals, free from the trappings of segregation or status. Even today, the photograph is startling for its sheer number of highly influential musicians from several different jazz eras. This regal cross-section includes trombone pioneer Miff Mole, swing-era drummer Gene Krupa, bebop inventor and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, idiosyncratic pianist Thelonious Monk, saxophonist-composers Benny Golson and Gigi Gryce, drummer Art Blakey and pianist Horace Silver, both hard-boppers, and bass modernist and composer Charles Mingus.

No less extraordinary is the inclusion of saxophone revolutionaries Bud Freeman, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and Sonny Rollins, as well as three superb female artists—vocalist Maxine Sullivan and pianists Mary Lou Williams and Marian McPartland. Also on display are pockets of drama. Gillespie, a notorious cutup, stuck his tongue out just as the camera’s shutter came down. Trumpeter Roy Eldridge was caught turning to laugh. Trumpeter Rex Stewart is the only musician with his instrument tucked under his arm, and Gerry Mulligan craned his neck to be seen. Monk and Mr. Rollins are the only ones wearing sunglasses. The college-age men who made up a sizable portion of Esquire’s readership in 1959 flooded the Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island that summer with dates in tow. Many also bought Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue,” Art Blakey’s “Moanin’” and Dave Brubeck’s “Time Out”—top-selling albums that year. “None of us had any idea that the photo was going to be famous,” said Mr. Golson in a phone interview. “After Esquire came out, we felt like human beings. We were considered special.” The book features for the first time Kane’s 70-plus outtakes from the shoot, along with six contact sheets.

The never-before-seen images of jazz musicians milling about reveal that Kane used two locations on East 126th Street—one on the stoop of No. 52 and the other at No. 17, a block and a half apart. Ultimately, the image from No. 17, with a more interesting architectural backdrop, was chosen for Esquire’s centerfold. Why Kane moved from one stoop to the other and how he kept all the musicians together remains a mystery. Included in the book are images taken that day by jazz bassist Milt Hinton, who had brought along his camera. His photographs provide lively images of Kane and Esquire graphics editor Robert Benton trying to manage the chaos from across the street. Before the shoot, Kane spent days scouting Harlem sites near train and subway stops. According to Mr. Golson, Kane reached out to the jazz writer Nat Hentoff, whose address book was fat with phone numbers. Kane also urged the musicians to tell other artists in their networks about his plan.

“When I saw how many musicians were there that morning, many of whom I knew only by name, I realized I was in some deep company,” said Mr. Rollins, the other surviving jazz musician from the photograph. “Art Kane had a hard time getting us to stop talking with each other. It was quite a social moment for us.” In truth, 58 musicians were supposed to be in the photo. Pianist Willie “the Lion” Smith was in a corner bar when the final image was taken and missed being included in the tableau. “It was hard getting guys out of that bar,” said Mr. Golson. “We were on that block from 10 a.m. until around 2 p.m.”

According to Kane’s text in the book, the musicians were the ones who positioned themselves on the stairs and sidewalk, not Kane or his assistant. Basie sat on the curb with the 11 children who insisted on being in the photo. It’s as if the jazz artists knew instinctively what setup would look best. At the time, Mr. Rollins was living on New York’s Lower East Side and practicing on the Williamsburg Bridge. “The photo in Esquire showed great respect for jazz and jazz’s humanity,” he said on the phone. “We thought, ‘Wow, we’re being respected.’ Suddenly, we were being seen the way we saw ourselves.”