![]()

GRAMMY

Magazine - June 29, 2004

The

Terminal Brings Classic Photo Into Relief

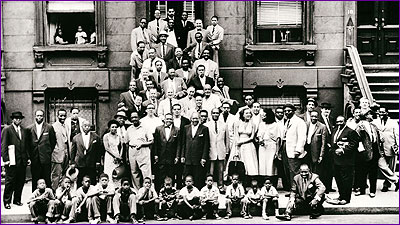

Steven

Spielberg film uses renowned jazz photo "A Great Day In Harlem" to

jump-start its plot

GRAMMY.com

Dave Helland

|

For detailed photo and caption info click here

|

An Eastern

European tourist flies to the United States to get saxophonist Benny Golson's

autograph. But by the time he lands, a military coup back home has, through the

vagaries of diplomacy and foreign policy, made him stateless, his passport

worthless. However improbable, he ends up stuck in an airport for a year.

That's the

plot of Steven Spielberg's new film, The Terminal, starring Tom Hanks

as Viktor Navorski, who comes to the United States to complete his father's

collection of autographs by the jazz musicians pictured in the classic 1958

photo known as "A Great Day In Harlem."

If the plot

seems far-fetched, you underestimate the fanaticism of foreign jazz fans and

the iconic status of that oft-reproduced photo. "A Great Day In

Harlem" is to the jazz world what a Mickey Mantle rookie baseball card

might be to a baseball fan.

"When we

took that picture, nobody thought it would become famous, nobody," recalls

Golson, who is frequently asked for his autograph and occasionally asked to

sign a reproduction of the photo. He was invited to the shoot by then- Down

Beat reviewer Nat Hentoff. "When I got there I wondered why I was

there. I was a nobody. I think I only knew four people: Dizzy Gillespie, [who]

I was playing with, Art Farmer, Johnny Griffin, and Sonny Rollins."

But Golson

went on to become one of the most-often covered composers in jazz, for his

works "I Remember Clifford," "Along Came Betty," and

"Killer Joe." He has a scene in the film — playing in a Ramada Inn —

which led to a new record, Terminal 1, released June 22. "I

didn't want to infringe on his title so my title was a little more specific to

commemorate doing this thing with Steven [Speilberg]," explains Golson.

"The CD never would have happened had he not asked me to be in the

picture."

How the photo

came to be shot is documented in Jean Bach's 1994 film, A Great Day In

Harlem. Esquire art director Robert Benton approached another art

director, Art Kane (www.artkane.com),

to contribute photos for an issue devoted to jazz. Kane thought of getting

"every jazz musician we can possibly assemble." Word went out to

publicists and producers at small jazz labels. On the appointed day and hour

they began assembling, no small feat, as one of the musicians pointed out: He

didn't realize there were two 10 o'clocks in the same day.

|

|

Bassist Milt

Hinton, who never went anywhere without his still camera, also brought an 8mm

movie camera. Bach interspersed these stills and movie footage with interviews

conducted in the early '90s of surviving musicians, Hentoff, Kane and others

instrumental in making the photo happen. Hinton's pictures show musicians

milling around, greeting not just old friends but also their mentors, and

paying little attention to attempts to pose them. Kane and his assistant Steve

Frankfurt were literally trying to herd cats.

But gradually

the musicians took their places along the sidewalk and up the steps of this

classic Harlem brownstone. Basie sat on the curb with a dozen kids from the

neighborhood. Other children looked out the windows. Briefly, 56 pairs of eyes

looked at the camera — all but Roy Eldridge, who looked over his shoulder at

Gillespie — and Kane snapped his picture, arguably the most important piece of

film in jazz history.

The musical

connection between people like trumpeters Gillespie and Eldridge, who stand

next to each other, and tenor saxophonists Rollins and Coleman Hawkins, who

stand near each other, is evident in the final photo. "A Great Day In

Harlem" shows the development of the music, beginning with the pre-jazz

era represented by stride pianist Luckey Roberts; the early days of jazz that

was played by musicians like drummer Zutty Singleton of Armstrong's Hot Five,

trombonist Miff Mole of Red Nichols' Five Pennies, and fiddler Stuff Smith, who

played with Jelly Roll Morton; swing era drummers like Gene Krupa, Sonny Greer

and Jo Jones plus Count Basie and members of his Old Testament Band, Buck

Clayton and Jimmy Rushing; and modern stylists like Thelonious Monk, Charles

Mingus, and Gerry Mulligan. Near the top of the steps are drummer Art Blakey

and two men who would soon join his Jazz Messengers: Art Farmer and Benny

Golson.

"There's

only about seven or eight of us left now," says Golson. But his partner in

the Messengers and later their own Jazztet had a different take on it when Bach

filmed them.

"We don't

think about people not being here," said the late Art Farmer. "If we

think about Lester Young, we don't think, 'yeah, Lester Young was here but he's

not here anymore.' Lester Young is here. Coleman Hawkins is here. Roy Eldridge

is here. They are in us and they will always be in us."

(Dave

Helland regrets that he didn't start collecting jazz musicians' autographs in

pictorial history books until 1980.)